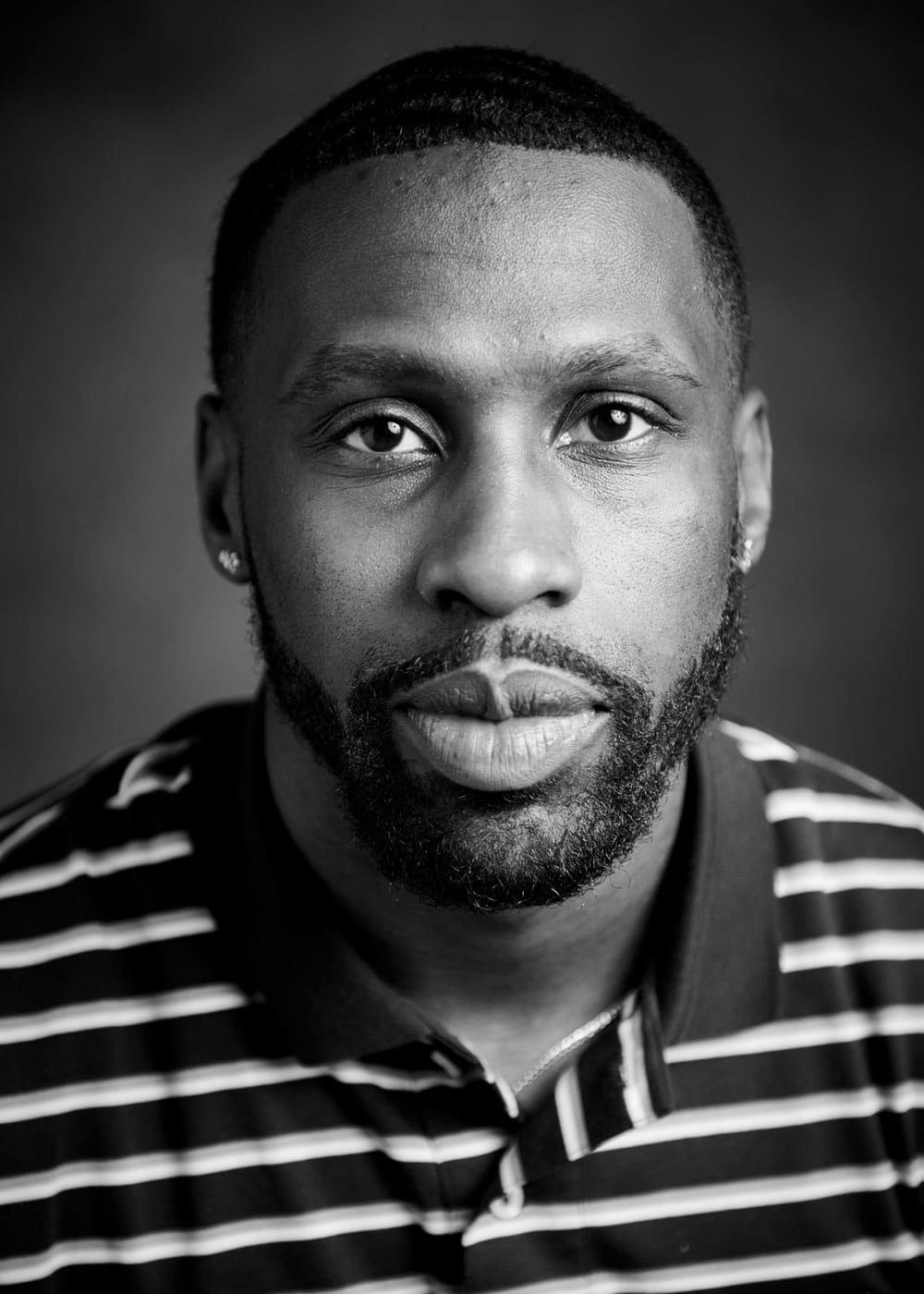

Gatluak came to the U.S. as a refugee from South Sudan.

He and his family left their home when he was a child and moved to a refugee camp where there was no access to clean drinking water—or really any of his basic needs. There was no one to look after him when he was sick and no one to give him an education. He was taken from his family and put into military training, forced to serve as a child soldier at six years old.

“It was a long journey and a devasting situation,” he says.

Eventually, Gatluak was reunited with his father and brother and they moved from camp to camp before coming to South Dakota and then to Nashville.

“I did not have an education at the time when I came here. I didn’t know how to do anything.”

He was living in East Nashville and working across the river at the Opryland Hotel. He’d take the bus from East Nashville to downtown to Murfreesboro Road to Opryland to get to work, but late at night when he was coming home, the bus didn’t make all those stops. He’d take the bus back to Murfreesboro Road and would walk from I-24 to I-65.

“That was a really challenging thing, and I did that for many, many months. My brother and I decided to buy a vehicle but at the time we didn’t speak English … did not write English. There was a lot of challenges that we had. But what else can you do? We needed to have a means of transportation. When we bought a car, I had to be the driver without knowing how to drive and without having a driver’s license or the insurance.”

So, Gatluak decided to learn English. He received his high school diploma then earned a Bachelor of Science degree in computer science from Tennessee State University before pursuing a master’s degree in public service from Cumberland University. Working two jobs and with a newly-earned college degree, he was ready to find someone to share his life with.

“When I was living here, I was going to school and I was working full-time. I didn’t socialize. I [couldn’t] just go to anyone and say, ‘Can I marry you?’ I also didn’t like the African tradition of an arranged marriage.”

He remembered a girl, Nyakuma, that he had loved as a young boy in South Sudan, so he asked his family back home to find her—and they did. After 10 years, she was still living in an encampment. The two married and he brought her to Nashville, teaching her English in their apartment.

Neighbors started to hear about how he could teach others to read, speak and write in English, so they began to come to his home for lessons. But these lessons and his home became a place for him, Nyakuma and other immigrants to explore what it means to be a refugee and how they can work together to address the diverse needs of their community.

“That’s the beginning of the Nashville International Center for Empowerment.”

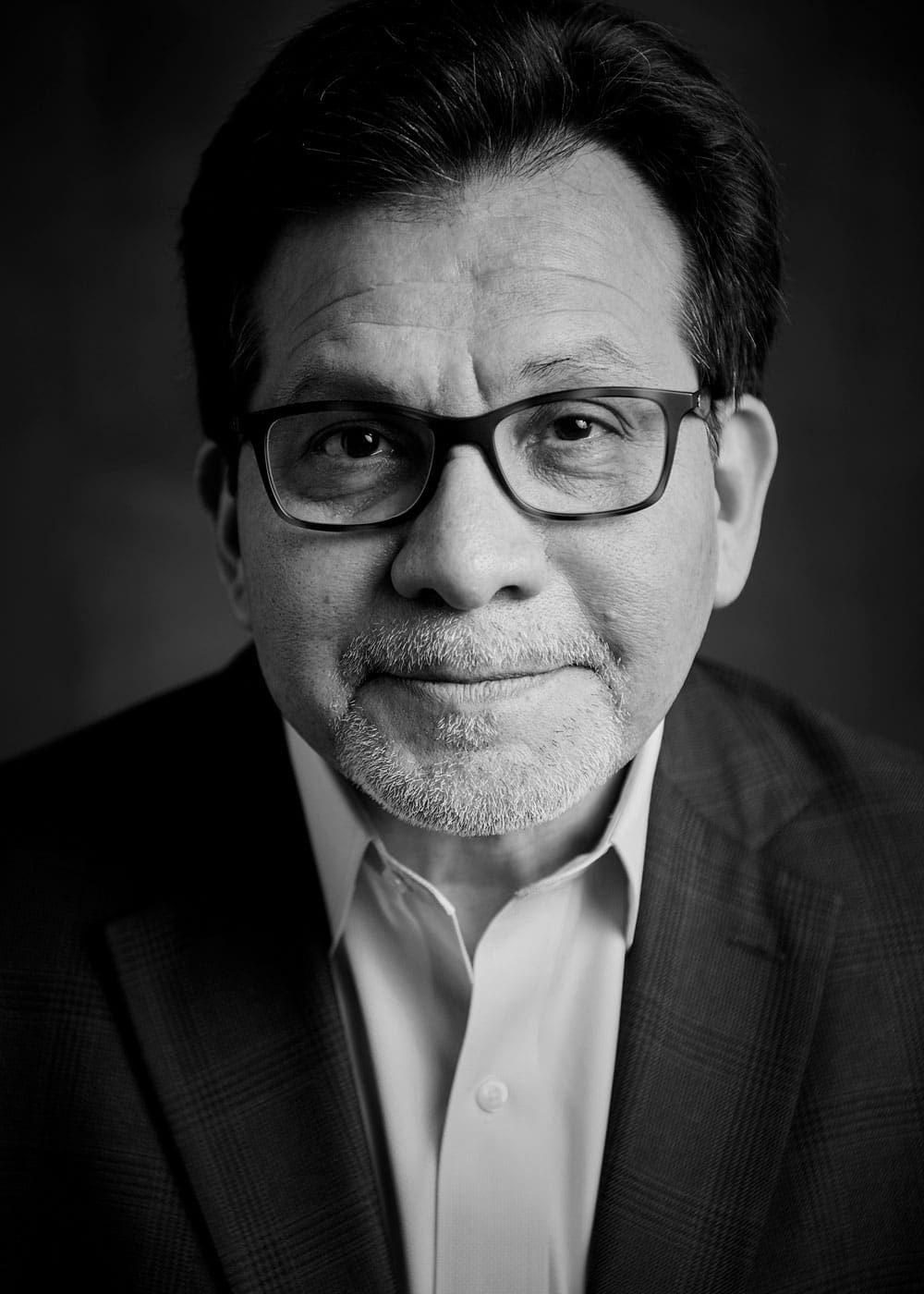

In 2005, now-president and CEO Dr. Gatluak Thach joined together with a group of refugee leaders and native-born Nashvillians to begin an organization that helps new immigrant communities overcome barriers of exclusion and marginalization.

“I said, ‘Wow, I need to run a place where I can teach these people English.’ There was no institution or organization at the time. I took off time from my workplace so that I could meet all the documentation. Then, I had to look for a funder.”

That’s where United Way stepped in and began investing in the Nashville International Center for Empowerment.

“Through NICE, refugees and immigrants who have lived through marginalization, exclusion and entrenched discrimination in their homeland are able to rebuild their lives with dignity here in the United States,” he says.

Now each month, the organization that he and his wife started in their apartment, serves nearly 3,000 people from more than 72 different nationalities.

“We became a model that people in the community and outside wanted to adapt. I will tell you: It enriched my life. It made part of my mission of giving back to the community and really giving back to people who have done nice for me. I have been a part of the community trying to figure out how we can move forward, how we can empower those that are here and try to connect all the dots.”

He says language and culture are some of the biggest barriers that refugees face when coming to Nashville.

“They have to support themselves, support their family and support the community but you cannot unless you have a means of communication. That’s one of the things that we wanted to make sure that our clients have: accessibility to language. The greatest gift this country offers to refugees and immigrants is that of agency: the ability to make decisions about their own lives.”